Five weeks into the semester, student numbers at Meserete Kristos Seminary continue to rise (now at 200). Some students were unable to travel five weeks ago due to violence in their part of the country, with killings still happening regularly. Overwhelmed teaching writing and speaking skills to 118 students, I hope no more students show up, but if they do, we faculty are to welcome them into our classes.

My students are mostly delightful, eager to learn, excited about having a foreigner like me teach them English, always ready to engage in conversation, filled with questions (edited here):

- Where are you from?

- How many children do you have?

- How is Ethiopia?

- What makes you happy?

- What food is popular in America? (When I said “Pizza,” the student asked, “What’s that?”)

- How many years have you been teaching?

- How can I improve my English?

- Can you teach extra classes at night?

- Can you help me with money? Shoes? A computer from the U.S.?

- Have you accepted Jesus as your Savior?

- When did you come to the Lord?

- What is your ministry in church?

We chat before class, or on the campus grounds, or more frequently during lunch and dinner in the dining hall. I eat with students most days (and join faculty twice a week). I take an occasional walk with students and get invited for coffee. When students aren’t asking me questions, I’m asking them—about what they’re learning in their other classes, about their families, English in high school, ethnic groups in Ethiopia, the political turmoil, their hopes for the future.

The most stunning question from a student hit me hard (unedited):

·

How you don’t start class by praying God?

Well now, I

certainly do, since that is the expectation. I ask students to lead in prayer

as well. They pray in their ethnic languages, mostly Amharic and Oromo, and

sometimes in English. The room fills with a chorus of “Amens,” and we then

begin learning.

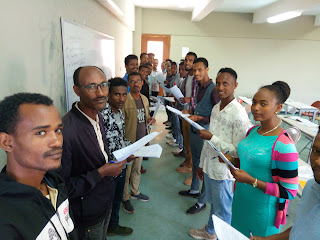

My 118 students are first and second-year students, divided into three groups by when they started at the seminary (not by language proficiency, which would make for more effective learning). Seven are international students—five refugees from Eritrea, who fled religious persecution, and two refugees from South Sudan, who fled civil war. About 10% are female. This low number shocked me at first, but when Rose Shenk and Bruce Buckwalter, former MCC country reps in Ethiopia heard this, they told me that was progress!

The majority of my students are in their mid-twenties, but 20% are in their thirties, and a handful are forty or fifty. Most cannot afford the school fees (around $2,500 for tuition, room, and board for the year). Some left their full-time ministries—as pastors, evangelists, and teachers—to obtain a B.A. degree in Bible and Theology, Mission and Intercultural Studies, Peace and Development, or Leadership and Management. Some are sponsored by their home congregations and will return to work there after getting their degrees. Some receive scholarships or take part in the seminary’s cost-sharing program.

The students’ religious fervor became quickly evident when I read their hobbies on the info form that they filled out for me. In addition to playing football, listening to music, reading, and watching TV, a large percentage like reading the Bible and praying in their free time. One student mentioned drawing, one cooking, and one washing his clothes!

Many of my students come from farmer families in rural areas, where everyone works on the farm, and where there may not be indoor plumbing. Many come from large families. Bob with his eight brothers would fit right in, as 20% of my students have eight or more siblings.

Ethiopia is a big country, and many students are far from home. Travel takes both time and money, so it doesn’t happen often for those from far away. Most of my students live in the dorms on campus (one for males and one for females). One-third of my students are married and have children of their own. Their commitment to their studies is evident since it means months away from their spouses and children.

How can I learn 118 names in a few weeks’ time? (I meet each class only once a week for three hours.) First, name cards on the desks. Second, photos of the students holding their name cards that I could look at before class. This week, I gave up the name cards, knowing about 90% by now. I hope the other 10% sinks in soon! When I meet students in the cafeteria, the context is different, and I don’t always remember which class they are in, let alone their names. I’ve had to humbly and apologetically ask names again and again. But my students seem pleased with the attention I’m giving.

This week I wrote down the meanings of all their names. Students in the dining hall helped me. Some names are Biblical, like Amanuel, Adamu, Bethlehem, Daniel, and Yosef. Others may have a religious or non-religious connotation—Dinsa (healer), Dugasa (truth), Feyera (deliverer), Fikadu (love), Girma (glory), Masgana (thanks), Selam (peace), Tamiru (miracle), Tesfaye (hope), Wakgari (God is good), Bakila (fruitful), Biftu (sun), Dereje (grow), Gemechu (happy), Habtamu (rich), Kefyalew (highest), Leta (branch), Mezgebu (treasure), Obsa (opposite), Takele (guard), Wondimu (brother).

My students and I are having fun in the classroom, and I’m even enjoying the effort it takes outside of class to mark the writing of 118 students, knowing that the writing process works and that most of my students will improve their skills over time. (More about English language teaching in Ethiopia and Meserete Kristos Seminary in future blog posts). To summarize, “I feel invigorated by my students!” (Of course, I happen to be writing this on a good day!)