I love languages! Amharic is no exception. Though my Amharic is rudimentary, I’ve been able to chat just a bit with people here in Ethiopia who may not know English. What fun it has been!

I’m glad I discovered the U.S. Foreign Service’s online Amharic lessons while still in Mexico. I’m also glad I bought this book to bring with me.

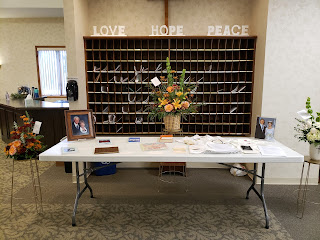

But I couldn’t have done it without Bethlehem Bizuwork! Beti and I began at Meserete Kristos Seminary the very same day—September 13 of this year. My Amharic lessons with Beti began the next day. It’s been a joy to spend time with this cheerful young woman, and I am truly grateful for all she has taught me, not only about Amharic but also about Ethiopian culture. I treasure our friendship.

I find the language and culture connection fascinating. I have dabbled in half a dozen languages in the nine countries in which I have lived. Learning a language can give hints into the culture. And sometimes it’s just fun to notice the differences in how we say things.

- Ethiopians are expressive. Students (and others) often tell me, “I love you” or “I love you so much”—not a typical expression from student to teacher in my culture.

- Nothing is a problem in Ethiopia. I hear “Chigir yelem,” or “It’s no problem” every single day. It’s the first Amharic expression that I taught Bob. I think many Ethiopians are more easy-going than I am.

- Greetings are tricky. When I say “Good morning” or “Hello” to my students in English, they respond with “I am fine.” (I want to say, “But I didn’t even ask you how you were!”) The common greeting in Amharic is more “Are you fine?” than “Good morning.”

- The other response to a greeting is “Thank God.” It means, “I am fine, thank God.” Ethiopians may more directly express gratefulness to God than we do in our culture.

- “Ayzosh” (to a female) or "Ayzoh" (to a male) is a common expression of encouragement. It means “Take heart” or “Be strong.” I heard it many times after my mother died, but I hear it in other contexts as well. I use the plural form when my students need a boost in their language learning. I tell them “Ayzuachu!”

- “What can I help you?” my students ask before or after class. They want to carry my bag or my stack of papers. I usually decline, but the offers are sweet.

- “I very thank you.” “God is very help me.” My college writing teacher, Omar Eby, taught us to never use the word “very.” (He found it meaningless.) In Ethiopia, the Amharic word for “very”—“bet’am”—can be added to almost any sentence. Sorry, Omar.

- Ethiopians say “Sure” or “Of course” more than we do in our language. Particularly one student, Samuel, says “Of course” in response to almost every question I ask him. Just for fun, I try to respond to all his questions with the Amharic equivalent—“Ekko!”

- “T’uro naw”—“It is good” tops the list of oft-used expressions. Is it that Amharic has fewer adjectives, or is it that everything is simply good?

- Another high-frequency word is “Ishi,” meaning “OK.” I love the sound of that word! It’s the second Amharic word that Bob learned from me. We now say it all the time.

I could go on, but since I’m leaving Ethiopia tomorrow, I’ll wrap this up. I want time to tell everyone “I love you” and “I very thank you.”

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)